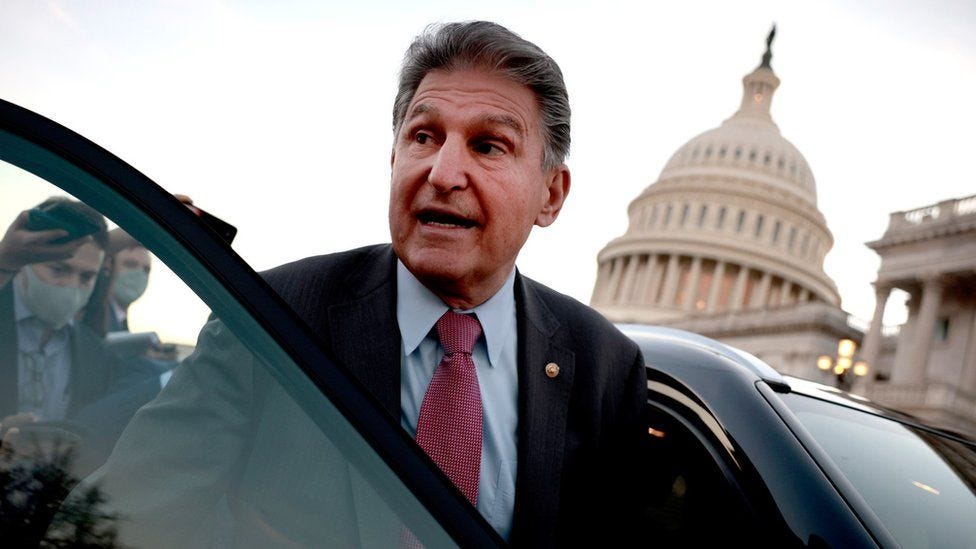

Joe Manchin and our Feeling of Being Stuck

Sen. Joe Manchin today announced that he would not support President Biden’s “Build Back Better” plan. For Democratic activists, the White House, and all who tacitly agreed to let Manchin essentially conduct the debate about this legislation for a whole year, this is perhaps the most frustrating event of Biden’s first year, and one that has already created fears of an electoral bloodbath for Democrats in 2022 and beyond.

Of all the institutional actors gnashing their teeth today, frustration from the White House is perhaps the most appropriate. According to Press Secretary Jen Psaki, Manchin had assured the president of his eventual support for some BBB framework a while back. Psaki uncharacteristically called out Manchin today by saying that his decision was “at odds with his discussions this week with the President, with White House staff, and with his own public utterances.”

For progressive and Democratic activists, frustration is more a product of poor expectation management than of an actual betrayal from Manchin, who was never on their team to begin with. Those who worked to elect Joe Biden, to maintain our slim House majority, and to achieve our even slimmer senate majority, were either unwilling or unable to state the obvious fact at the beginning of 2021: that Joe Manchin is a conservative Democrat in a Trump +40 state, whose personal beliefs and political incentives were virtually diametrically opposed to those of the progressive base.

There are many reasons the expectations of activists were heightened:

They believed that because Democrats were “in charge,” the government’s actions would be bold, numerous, and proportional to our problems. In the waning weeks of the Trump presidency, the country seemed to be approaching “failed state” status: mass death, historic joblessness, the right wing’s framing of the pandemic as just another culture war venue rather than as a public health crisis requiring personal sacrifice, daily bombardment of disinformation from America’s most popular news network, and most dangerous of all, an out-of-control, narcissistic president who was working to worsen these conditions, while all but vowing violent retribution if he was voted out of office for them (which, it turns out, was not a bluff.) In such a situation, we believed that anyone in their right mind would support swift, bold, long-lasting actions from the federal government to meet these colossal challenges. We assumed Joe Manchin was in that camp. At first, he was, but his personal and political incentives instruct him not to be a ready-vote for an increasingly progressive Democratic caucus.

We still erroneously see the Democratic Party as a monolith. In 2016, political scientists Matt Grossman and David Hopkins reconfirmed something that political analysts had repeated for decades: Republicans are largely united by their shared ideology while Democrats are united (or often disunited) by their reliance on a tenuous coalition of left and center-left interest groups. These different “glues” that bond each party together matter: when Republicans govern, they typically start with rigid ideological commitments and revise from there. When Democrats govern, they must cast their net wider, making sure legislation and actions by the government please as many of their (often conflicting) groups as possible. No such comprehensive analysis I’m aware of has been done of the party structures since then, but we can safely say that the Democratic Party has inched closer to the Republicans in its ideological commitments in recent years, signaled by the highly influential campaigns of folks like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, and a number of progressives in the House like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Katie Porter. Still, the Democratic Party is not a monolith, and its congressional majorities, while consisting primarily of progressives, cannot survive without providing space for moderates and even sometimes a handful of conservatives. The fact that one or two of the Democrats occupying that space can, and so often do stall or block legislation should not be surprising, when one considers the historically progressive nature of Biden’s agenda.

We are operating as majoritarians in an anti-majoritarian institution. Congress was designed to thwart national majorities. In recent years, it has been more widely understood that much of our constitutional framework was enacted to protect slavery. A related but equally undemocratic reason was the simple fear of majorities in general. In the Federalist Papers written by Madison, Hamilton, and Jay, the pseudonymous author “Publius” is quite explicit about how dangerous national majorities could be. In Federalist 10 he writes: “democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths.” The senate happens to be one of the most anti-democratic institutions of the federal government. It is frustrating to witness the stalling of legislation that would help nearly all Americans by one senator who represents the nation’s 40th most populous state. Yet veto power is built into nearly every corner of our system. If we had 51 or 52 Democratic senators, that probably would have been enough of a majority that Manchin could vote against the bill and no one would care; he certainly would not have been its main negotiator. Alas, West Virginia’s senatorial representation is protected by its state borders, as is every other state in the country.

So now what?

BBB could come back in a stripped down form in 2022, or Democrats could chop it into smaller pieces, put each up for a vote, make Republicans vote against each popular program, and run against them on that in 2022 and ‘24. But this reminds us of a truism in politics, that folks need something to vote for, and not just against. Further, voters who are paying little attention to why or why not legislation passes will have no patience for the argument that “98% of Democrats wanted these great things but we couldn’t get it done” when the country had just “put them in charge.”

If history is any guide, frustratingly, American voters will punish the party in charge for not getting popular things done by voting for the party that wants to do the exact opposite of those popular things. Moderates do this in the name of “giving the other party a chance”; progressives will lend less support to the Democrats, whether in their votes, their work, or their defense, because they feel disappointed in not getting what they want.

While it is perfectly understandable for those barely paying attention to take either of these routes, activists have a responsibility to be more strategic and indeed, to be more realistic. If we lose any senate seats in 2022, Joe Biden will be dealing with Mitch McConnell, not Joe Manchin. One might say “well what’s the difference if nothing is getting passed anyway?” To this charge I would offer the fact that much has gotten done in Biden’s first year, among them, the initial stimulus checks and a bipartisan infrastructure bill with 20 GOP votes; an unthinkable feat for anyone living through American politics the last decade.

“Things could be worse” is an admittedly uninspiring rally cry, given how traumatic politics has been in recent years. I imagine this is how the Democratic party will present the choice in 2022.

The simple truth is, politics and progress are grueling, long-term endeavors that take years to achieve, particularly in a system like ours. How many among us have striven for personal progress in our lives, in health, relationships, finances, and personal betterment, only to face numerous setbacks, disappointments, and back-to-the-drawing-board moments?

Each of us is just one person.

Consider the size and scope of the United States: 350 million people, tens of thousands of different governments at all levels, centuries of rules and procedures frozen into place to stymie change. The idea that we have two paths: that this should all be easy, or that we should give up, is to ignore all the ways progress is ever achieved.

Our majorities are slight and veto power is contained in the hands of Democrats whose incentives do not align with those of the more progressive party as a whole. Therefore, whatever progress could be achieved on Biden’s agenda in 2022 is likely going to come in slow drips rather than in the type of splash we were hoping for with the full BBB framework. We as activists ought to always be attentive to these incremental inches toward a more perfect union.

For the midterms, we have a small, but non-zero chance of maintaining or growing our majorities, especially in the senate. We need to have the wisdom and the courage to not let our emotions get the better of us right now; if we had had 51-53 Democrats in the senate this year, we would have passed BBB (and probably a more comprehensive version than the one Manchin cut it to). If we can get there, and somehow garner the right message and activist enthusiasm to turn out the vote in the house, we can make progress a bit more likely for the second half of Biden’s term. I say, let’s get to work.